(Stabley 1959)

The needs washed construction consists of a form of the verb need (or want or like) followed by a passive participle. For example, in sentence (1), needs repaired is an example of this construction; it has present tense needs followed by the passive participle repaired:

1) The car needs repaired.

In standard English, (1) would not be acceptable. Instead, speakers would either use an infinitive (a verb form with to), as in (2a), or a verbal form ending in -ing, as in (2b):

2) a. The car needs to be repaired.

b. The car needs repairing.

The verb most commonly associated with this construction is need. However, many other verbs are also possible, particularly want and like, as in the following examples from Murray and Simon (2002):

3) Cindy, this one [baby] just woke up and probably wants fed.

4) [The dog] sure does like petted.

This construction is also sometimes referred to as need + V-en, where V stands for a verb, and -en indicates that the verb has a passive participle ending (even though this passive participle ending may be -ed, as in fixed, -n, as in thrown, or something else).

Contents

Who says this?

Syntactic properties

Historical Origins

Recent survey results

Important vocabulary for this page

References

Who says this?

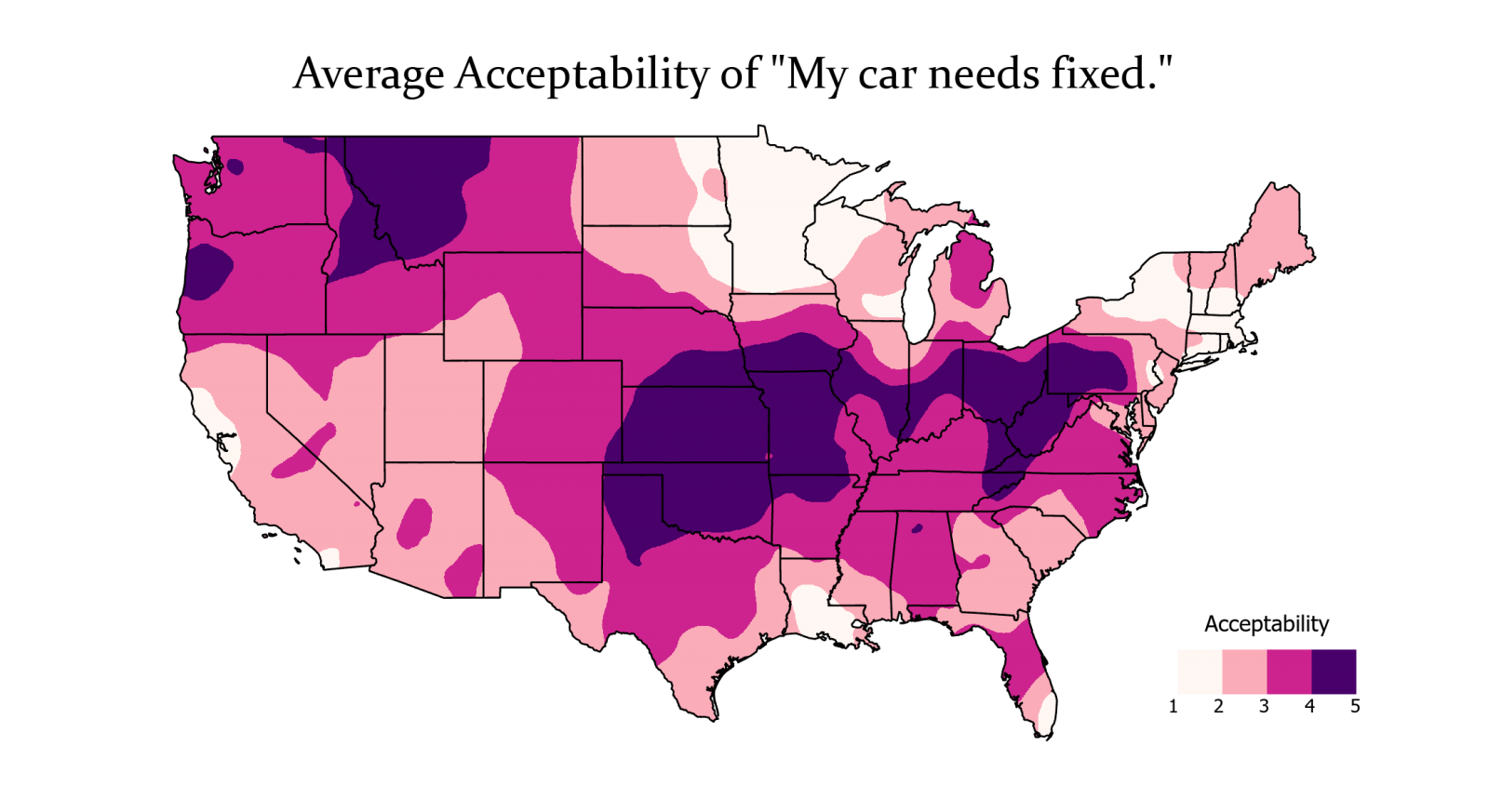

The home of the needs washed construction is the Midlands (Wood et al. 2022): Missouri, Illinois, lower Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, western Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. The core region, where it is accepted at the highest rates and in the widest variety of sentences, is in Indiana, Ohio, and Western Pennsylvania (Wood et al. 2022). Duncan (2024) points out that there has long been a "strong association between the Pittsburgh area and the [needs washed construction]," citing Edelstein (2014), Johnstone (2009), Tenny (1998), and Strelluf (2020, 2022). There are also pockets of speakers in Arizona and in the Northwest, including Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. In acceptability surveys, the needs washed construction is strongly, overwhelmingly rejected in the Northeast; it is also consistently rejected, but not quite to the same degree, in Southern California and in the upper Midwest, including Minnesota, Wisconsin, and most of Michigan (Wood et al. 2022).

Two sociolinguistic factors that seem to affect acceptability ratings of the needs washed construction are race and population density. Wood et al. (2022) and Duncan (2024) both find that while white speakers accept the construction at higher rates than speakers of other races, this effect is not as significant as other factors. Wood et al. (2022) find that the geographic patterns of acceptance are much more clearly defined among speakers that live in rural areas (in other words, the association between the construction and the "core" regions is weaker in cities). However, Duncan (2024) points out that sociolinguistic factors don't affect acceptability ratings as much as purely linguistic factors, such as the syntactic and semantic characteristics of the verb being tested (in place of need in the construction).

This construction is also strongly attested in the Englishes of Scotland and Northern Ireland (Duncan 2024; Strelluf 2020, 2022; Smith et al. 2019; Brown and Millar 1980), which are believed to be its historical source. See more on this connection in the Historical Origins section.

The following map shows the average acceptability of My car needs fixed on a scale of 1-5 (1 being unacceptable, 5 being fully acceptable) from surveys conducted by Wood et al. (2020).

Map created by Josephine Holubkov on May 30th, 2020

See our interactive map below to explore some of the raw data in more detail.

Syntactic Properties

Allowed verbs

For a long time, it was believed that need, want, and like were the only verbs that could be the main verb in this construction. Recently, however, Duncan (2024) conducted a large-scale study that shows that 18 additional verbs receive high acceptability ratings in the core US region (Indiana, Ohio, western Pennsylvania). These include deserve, require, and (could) stand, as in the following example sentences from Duncan (2021, 2024):

5) a. I don't think he deserves fired.

b. This paperwork requires completed.

c. His room could stand cleaned up a bit.

Other allowed verbs include love (corroborated by Wood et al. 2022), hate, prefer, and expect. Duncan (2024) reports that out of 116 verbs tested, those relating to choice, desire, sentiment, and necessity were accepted at much higher rates than verbs in other semantic groups (such as arranging for future events or preventing a future event).

It is worth noting that although Duncan's (2024) study shows similar overall acceptability ratings between US and UK speakers, the set of allowed verbs is not exactly the same. UK speakers who have the construction with need, want, and like did not accept all 18 of the additional verbs that US speakers in the core region accepted. The allowed verbs also differ between Scotland and Northern Ireland. Duncan (2024) points out that this discrepancy could indicate that the dialects in these three countries might have undergone diverging innovation (that is, might have changed over time in different ways) with respect to the needs washed construction, but that more research would be needed to confirm this.

Purpose clauses allowed

Purpose infinitives are infinitives in which the word to can be interpreted as in order to, as in I work hard to please my boss. According to Edelstein (2014), who provides the examples in (6), purpose clauses are possible with the needs washed construction:

6) a. The new set still needs washed to kill germs.

b. Your brain needs fed to work out.

c. He wants cuddled to go to sleep.

The needs washed construction shares this property with its standard English counterpart, as in The new set still needs to be washed to kill germs.

Non-volitional subjects allowed

Edelstein (2014) also claims that the subject of the construction is not necessarily volitional, even when the verb is want or like, both of which would typically have volitional subjects outside of this construction. She cites the sentences in (7) as examples of this construction with non-volitional subjects:

7) a. That Doctor of hers wants reprimanded for missing that one!!

b. All kids want told off from time to time.

c. [a particular plant...] is easy to grow, except that it ‘likes watered every day’.

(7c is originally from Murray and Simon 2002:41)

In these sentences, it is obvious that it is not the doctor's desire to be reprimanded, or the kids' desire to be told off, and, given the context, (7c) is probably not meant to express the desires of a (perhaps anthropomorphized) plant. In these uses, the meaning of the verb comes quite close to 'need.'

This distinguishes the needs washed construction from its standard English counterpart because want and like generally don't allow non-volitional subjects.

Auxiliary need need not apply

The word need can be an auxiliary or a main verb. Auxiliary need is usually found in negated sentences, where it behaves like other auxiliary verbs: it precedes the negative particle not and forms the negation without the addition of the verb do, as in (8a). Main verbs require such do-support to form negation, as in (8b):

8) a. The car need not be washed so thoroughly.

b. The car does not need to be washed so thoroughly.

Edelstein (2014) points out that only main verb need is possible in the needs washed construction. Auxiliary need is not possible. This is shown by the fact that (9a) is unacceptable while (9b) is acceptable:

9) a. *The car need not washed.

b. The car does not need washed.

Verbal or adjectival passives?

A question many researchers have addressed is whether the participle in the needs washed construction is a verbal passive or an adjectival passive. These two types of passive participles can be difficult to distinguish because they use the same verbal form, as in (10):

10) a. The Minotaur is being defeated. (verbal passive)

b. The Minotaur seems defeated. (adjectival passive)

By-phrases:

One test that is traditionally used to differentiate between the two types of passives is compatibility with by-phrases. Only verbal passives are compatible with by-phrases. For example, (11a), which has a verbal passive, is acceptable, while (11b), which has an adjectival passive, is not:

11) a. The Minotaur is being defeated by Theseus. (verbal)

b. *The Minotaur seems defeated by Theseus. (adjectival)

Therefore, if the needs washed construction could take a by-phrase, that would be evidence that it involves the verbal passive. While Brassil (2010) claimed that needs washed sentences are generally incompatible with by-phrases, Whitman (2010) and Edelstein (2014) argue that by-phrases are, in fact, possible. For example, the sentences in (12) from Whitman (2010) and those in (13) from Edelstein (2014) are acceptable to many speakers:

12) a. The car needs washed, not necessarily by you, but by someone before the weekend.

b. I’ve written up the document, but before it goes out, it needs checked by Kim, Alex, and Sandy.

13) a. The baby wants cuddled by her mother.

b. The soul needs fed by creative, multi-dimensional teaching.

Bruening (2014) argues that by-phrases don't provide the most accurate test because there are attested examples of adjectival passives occurring with by-phrases. However, there are other reasons to think that needs washed sentences involve verbal passives.

Un- passives:

Passive participles can often take the prefix un-, creating forms known as "un- passives" (e.g. unwrapped, unmarked). The following examples from the web show that un- passives can occur in the needs washed construction:

14) a. Each kiddo gets a piece of candy that needs unwrapped. [Source]

b. Even the peaceful Water Garden has a secret that needs uncovered. [Source]

c. We moved into the new place last night but things still need unpacked. [Source]

Notice, however, that all of these un- passives come from reversible verbs (wrap → unwrap, cover → uncover, pack → unpack). Tenny (1998) finds that the needs washed construction cannot take un- passives that come from non-reversible verbs (wash → *unwash, paint → *unpaint, open → *unopen):

15) a. *The car needs unwashed.

b. *The house needs unpainted.

c. *The door needs unopened.

This pattern actually provides evidence that the passive participle in the needs washed construction is a verbal passive.

In English, the prefix un- can either be negative (unhappy = "not happy") or reversative (unwrap = "to reverse the state of being wrapped"). Negative un- always attaches to adjectives. Reversative un- always attaches to verbs, but it can't attach to every verb; generally, only verbs that denote a reversible action can take the prefix un- (hence the strangeness of forms like unwash and unpaint).

Because passive participles can be adjectival or verbal, an un- passive like unwrapped can have negative or reversative un-, depending on context. In a sentence like The gift was unwrapped, the word unwrapped could describe the state of the gift in the past (adjectival) OR an action done to the gift at a moment in the past (verbal). However, this is only possible because wrap is a reversible verb. An un- passive formed from a non-reversible verb, like unwashed, can never be a verbal passive. In a sentence like The car was unwashed, the word unwashed can only describe the state of the car in the past, not an action done to the car at a moment in the past. Un- passives of this type are unambiguously adjectival.

In (15) we see that this type of un- passives, which are strictly adjectival, cannot occur in the needs washed construction. In contrast, the examples in (14) show that the needs washed construction is perfectly compatible with those un- passives that have the capacity to be verbal.

Substitution:

Adjectival passives can always be replaced by an adjective, as seen in (16):

16) a. The Minotaur seems defeated.

b. The Minotaur seems angry.

Tenny (1998) points out that the participle in the needs washed construction cannot be replaced by an adjective, citing the following examples, which were unacceptable to Pittsburgh speakers:

17) a. *The clown needs funny.

b. *This house needs bigger.

c. *The wall needs clean.

If needs washed sentences involved adjectival participles, we would expect this kind of substitution to be possible.

Adjectival adverbs:

According to Edelstein (2014), certain adverbs that can precede adjectival passives do not occur naturally with needs washed sentences. For example, well may precede adjectival passives, as shown in (18a), but well may not precede the passive participle in the needs washed construction in (18b):

18) a. The letter seems well written.

b. *The letter needs well written.

(18b is originally from Edelstein 2014)

If needs washed sentences involved adjectival participles, we would expect (18b) to be possible.

The unacceptability of the sentences in (17) and (18b) suggest that needs washed sentences involve verbal passive participles rather than adjectival passive participles.

Implications for syntactic theory

Some linguists (Belletti and Rizzi 1988) have claimed that psych-verbs can only form adjectival passives, not verbal passives. Others (Grimshaw 1990) have claimed that agentive psych-verbs can form verbal passives, but non-agentive psych-verbs can only form adjectival passives. Tenny (1998) uses the needs washed construction to argue against both of these proposals.

Tenny (1998) finds that the needs washed construction is possible for some Pittsburgh speakers with psych-verbs and non-agentive by-phrases. Because she classifies the participle in the needs washed construction as an unambiguously verbal passive, she argues that non-agentive psych-verbs must therefore be able to form verbal passives. The following examples from Tenny (1998) were rated acceptable by some speakers:

19) a. Some people need saddened by tragedy, in order to achieve wisdom.

b. Nobody needs angered by the truth.

c. Nobody needs discouraged by the truth.

Therefore, she claims, the properties of the needs washed construction are only compatible with accounts that allow non-agentive psych-verbs to form verbal passives. As such, the needs washed construction has the potential to help us answer a long-debated question in syntactic theory.

Historical Origins

There is significant evidence to suggest that the needs washed construction comes from Scotland and Northern Ireland. Out of the entire English-speaking world, the construction is found almost exclusively in the US midlands, Scotland, and Northern Ireland, which points to a connection on its own; what's more, the US midlands and the Appalachian region saw a significant amount of Scots-Irish migration during the colonization of the Americas. To further investigate this potential connection, Duncan (2024) conducted a "geospatial analysis" and reports that communities with more Scots-Irish ancestry accept needs washed sentences at higher rates, which he argues "is suggestive of a founder, or cultural inertia, effect maintaining the [needs washed construction]" in regions of America with strong Scots-Irish ancestry. Furthermore, Duncan (2024) finds that US and UK speakers overall have very similar patterns of acceptability ratings and display similar constraints (in other words, they find the same features and variations unacceptable). He concludes that the needs washed construction is "effectively the same phenomenon in both nations."

Duncan (2024) argues that if the construction did come to the United States from Scots-Irish immigrants, we might expect it to exist in the dialects of other locations that saw a lot of Scots-Irish settler colonial migration, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. While the construction "is attested in regions [of New Zealand] with a high proportion of Scottish settlers," Duncan (2024) says, it does not exist anywhere in Canada or Australia. This is relatively surprising and poses a linguistic puzzle that has no solution as of yet.

Recent Survey Results

The interactive map below shows some of the raw data from our recent survey work.

Important vocabulary for this page

See the full glossary for linguistic terms relevant to other pages

Participle: A form of a verb that can combine with have or be to create various tenses and aspects. When past participles combine with auxiliary have, they form the perfect aspect, as in She has written four pages today. When passive participles combine with a form of be, they form the passive voice, as in The pictures were taken on Monday. In English, the past participle and passive participle of a verb look identical, but we label them differently because they have different functions. These two types of participle usually end in -en (eaten, taken), -ed (worked, baked), or -n (thrown, drawn).

See the full glossary for more on present participles.

Passive voice: A way of constructing a sentence without mentioning the entity that performs the action denoted by the verb. For example, the sentence The floors are cleaned every week is in the passive voice; any counterpart in the active voice would require the addition of an agent, as in Joe cleans the floors every week. In English, the passive voice requires a form of the verb be, such as is or was, and a verb in its passive participle form, such as cleaned. The standard English version of the needs washed construction involves the passive voice, as in The car needs to be washed.

Passive participle: The form of a verb that combines with a form of be to create the passive voice, as in Nothing was taken from my office, where taken is a passive participle. See entries on "Participle" and "Passive voice" above for further explanation.

Syntax: The way words combine to form phrases and sentences. Syntax studies the rules that govern the order in which words can be strung together, and, to look at it from the other direction, the positions that different types of words are allowed to occupy. For example, a verb's syntactic characteristics might be whether it takes a direct object and what types of phrases (e.g. noun phrase, prepositional phrase, verb phrase) the direct object can be.

Semantics: The study of meaning at a word-, phrase-, and sentence-level. Semantics involves both the way we glean meaning from a string of words and the way words are allowed to combine based on their meaning. For example, a verb's semantic characteristics might be what type of action or event it denotes, or whether its subject needs to be animate.

Volitional: A noun phrase is volitional if it refers to someone who is acting according to their own desires or will. For example, in the sentence Brutus murdered Julius Caesar, the subject Brutus is volitional, while in the sentence The hurricane killed many people, the subject the hurricane is non-volitional. The verbs want and like typically have volitional subjects, hence the acceptability of Mary wants long legs vs. the unacceptability of #The table wants long legs (although want can sometimes have a non-volitional reading, as in You'll want to turn left at the next intersection). It is therefore surprising that both want and like can take non-volitional subjects in the needs washed construction.

Auxiliary: Sometimes known as "helping verbs," auxiliaries like be, do, and have are used alongside main verbs to express tense and aspect, among other things. For example, in the sentence I am talking to Mary, the auxiliary am indicates that the event is taking place in the present, while in I was talking to Mary, the auxiliary was indicates that the event was taking place in the past.

Main verb: The verb that describes the primary action or state that the sentence is about. In the sentence I have talked to Mary already, the main verb is talked, whereas have is an auxiliary.

Psych-verb: A psychological verb, or psych-verb, is a verb that expresses a mental and/or emotional state (or event). For example, in a sentence like Mary loves her pet turtle, the psych-verb love expresses the emotional state of the subject (Mary). In a sentence like Mary's behavior angers me, the psych-verb anger expresses the emotional state of the object (me). When the object's emotional state is expressed, the subject is sometimes volitional (as in Mary is bothering me on purpose), in which case the verb is an agentive psych-verb, and sometimes non-volitional (as in That news really bothered me), in which case the verb is a non-agentive psych-verb.

Agentive: A noun phrase has an "agentive" role when it refers to the entity that initiates or performs the action denoted by the predicate. For an entity to be an agent, it must be acting intentionally. For example, in the sentence The truth angered Sally, the noun phrase the truth is non-agentive; although it is causing the "angering," it is an inanimate entity and therefore cannot be acting intentionally. By contrast, in the sentence The teacher angered Sally, the noun phrase the teacher could be agentive if the teacher in question was acting intentionally to anger Sally.

Page contributed by Zach Maher and Jim Wood on June 11, 2011

Updates/revisions: August 22, 2015 (Tom McCoy); June 12, 2018 (Katie Martin); June 14, 2024 (Sarah Sparling)

Please cite this page as: Maher, Zach and Jim Wood. 2011. Needs washed. Yale Grammatical Diversity Project: English in North America. (Available online at http://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/needs-washed. Accessed on YYYY-MM-DD). Updated by Tom McCoy (2015), Katie Martin (2018), and Sarah Sparling (2024).