(Morgan, Good Will Hunting)

Intensifiers are words like so or really, which modify another word (often an adjective) and convey that some property holds to a high degree.

1) She is really good at guitar.

2) She is so good at guitar.

In some varieties of English, wicked can be used as an intensifier in this way.

3) She is wicked good at guitar.

In (3), wicked expresses a meaning similar to really in (1) or so in (2), and does not carry the meaning ‘evil’ that it traditionally has as an adjective. We will refer to this as “intensifier wicked.”

Photograph provided by Elena Ungurianu

Who says this?

Intensifier wicked is characteristic of New England, especially Eastern New England, and is popularly used to represent New England in general or Boston specifically. The Dictionary of American Regional English (Cassidy and Hall 2013) lists intensifier wicked as “New England, chiefly Maine, Massachusetts.” Ravindranath (2011) studied 351 overheard examples in southern New Hampshire, and Crocker (2016) reports it usage-specifically in Rhode Island. Yale Grammatical Diversity Project surveys confirm the New England distribution. Wood (2019) shows that although intensifier wicked is judged acceptable by people across the U.S., it is rated much higher in New England than anywhere else. New England was, in fact, the only region that was picked out as statistically significant. This can also be seen in the maps in Wood et al. (2020). Wood (2023) used YGDP data to identify dialect regions from the bottom up, and New England was picked out as a clear, identifiable region. The characteristic that identified New England as distinct from other regions, more than any other, was intensifier wicked.

Map created by Jim Wood on June 13th, 2024

Syntactic Properties

With adjectives

The most canonical and common use of intensifier wicked is as a modifier of an adjective. It is commonly referred to as an adverb in this use, and has a meaning similar to very or really. Like very/really, it can modify predicative or attributive adjectives. Some examples of predicative adjectives with intensifier wicked from Ravindranath (2011) are shown in (4)–(5) below.

(4) That show was wicked awesome.

‘That show was really awesome’(5) Now that interest rates are wicked low...

‘Now that interest rates are very low…’

(Salem Five Bank, radio ad)

Some examples of attributive adjectives with intensifier wicked are shown in (6)–(8) below.

(6) We haven’t hung out in a wicked long time.

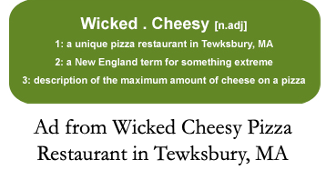

‘…a very long time.’(7) Wicked Cheesy Pizza in Tewksbury, MA

‘Very Cheesy Pizza…’

(first ad below)(8) Wicked Good Pet Cuddler

‘Very Good Pet Cuddler’

(second ad below)

Images from Ravindranath (2011)

Brown (2014) provides examples showing that intensifier wicked can modify adjectives expressing a wide variety of properties, including the ones in (9)–(14), illustrated with her attested examples.

(9) it’s like wicked far away (Dimension)

(10) he’s wicked selfish (Human Propensity)

(11) yeah it was wicked cold (Physical Property)

(12) there were wicked fast teams (Speed)

(13) I mean not like wicked good money (Value)

(14) Looking back on wicked old Facebook posts and pictures (Age)

The meaning of all of these example sentences is close to what the meaning would be if wicked were replaced with very. Speakers have the intuition, however, that wicked is higher on the intensity scale than very. For example, the threshold for wicked cold is colder than it is for very cold, so saying very cold might be appropriate in contexts when it's not cold enough to say wicked cold.

With verb phrases

Brown (2014) points out that intensifier wicked can occur with some verbs, including want, like, love, hate, need, and care, among others. She provides the example in (15):

(15) Starting to get very excited for Friday…I actually wicked miss @GlebusTwoThree (Brown 2014)

The maps in Wood et al. (2020) show that the sentence in (16) is widely accepted in New England, just like the examples with adjectives.

(16) I wicked want to go to that concert.

In these cases, wicked is roughly synonymous with really, so that (15) means ‘I actually really miss @GlebusTwoThree’ and (16) means ‘I really want to go…’

However, it cannot occur with all verbs. It only functions as a substitute for really as an emphasis of high degree. It cannot replace really in contexts like He really left, whose meaning comes closer to 'It is true that he left'. Some survey participants reported that in cases like (16), it would be more natural to use a verb phrase modifier wicked bad, as as in I want to go to that concert wicked bad. In general, uses of wicked with verbs could instead be replaced with wicked bad in this way. This is similar to really, which can generally be replaced by the phrase really bad at the end of a sentence, as in I want to go to that concert really bad.

With nouns

In this variety, wicked usually cannot usually modify a noun directly (see discussion of adjectival wicked below), although there are some contexts where it can. If a noun can be modified by very, then wicked tends to be possible as well.

(17) That’s wicked New England.

‘That’s very New England.’

In addition, intensifier wicked is sometimes possible if the noun itself refers to something that can be evaluated on a scale. For example, Ravindranath (2011) provides the example in (18) and an example similar to the attested example in (19):

(18) My desk is a wicked mess.

‘My desk is very messy.’(19) That guy who just walked by is a wicked jerk.

‘…is a big jerk.’https://live959.com/nine-wicked-awesome-words-only-massachusetts-residents-truly-understand/

Nouns that can be modified by wicked in this way tend to be nouns that can also be modified by big with the meaning 'to a large degree'. For example, a big jerk is someone whose has jerk-like characteristics to a high degree, and a big mess is not necessarily large in size, but possesses a high degree of mess-like qualities. These nouns can also be modified by such a, as in such a jerk or such a mess.

A wicked lot

Wicked can also be added to the expression a lot to form a wicked lot. The examples in (20) and (21) come from Ravindranath (2011). The YGDP surveys reported in Wood et al. 2020 included the sentence in (22), which robustly verified its acceptability in New England.

(20) I like her a wicked lot.

(21) She ordered a wicked lot of food.

(22) Jessie likes that band a wicked lot.

Wicked as a predicate adjective

Wicked does occur as a predicative or attributive adjective in some varieties of English, but this is a distinct use. Wood et al. (2020) point out that native speakers of New England wicked "find it to be distinct in acceptability”. The YGDP surveys included one sentence with wicked as a predicate adjective:

(23) # This coffee is wicked.

Comments on this sentence from participant surveys support its distinct status. The comments in (24) explicitly say that wicked should modify some other adjective, and the comments in (25) indicate that when it used as an adjective, it has a different meaning, such as the traditional meaning of ‘evil’.

(24)a.‘This coffee is wicked good' is used more often than 'This coffee is wicked’.b.'wicked seems more acceptable with another adjective, but is still in my mind acceptable here as it is clear to understand’.c.I wasn't sure about the first and last sentences in this set since most of the time 'hella' and 'wicked' are used to modify something.(25)a.evil coffee.b.'This coffee is wicked' is totally grammatical if and only if the coffee is sentient and malicious.c.'This coffee is wicked' is acceptable, but I'm not totally clear of the meaning of wicked here…

Wood et al. (2020) point out that “at best, it is a marked usage with an affected feel, unlike the intensifier usage.” They also point out that unlike genuine cases of intensifier wicked, there was no statistically significant regional variation found for (23).

In popular culture

Wicked frequently shows up as a marker of New England or Boston identity in popular culture. One famous example is in the film Good Will Hunting, where it appeared as a way of distinctly locating the events of the movie in Boston. The protagonist's friend says of him, "My boy's wicked smart." In the animation below, the caption also tries to reflect the Boston pronunciation through spelling.

Controversy over adjectival Wicked in Superbowl commercial

In other varieties of English, wicked can be used as an adjective meaning something like ‘cool’. Ravindranath (2011) provides the example in (26) (# added here to emphasize their distinct status):

(26) # This school has wicked parties!

For speakers of the New England variety, this usage has, at best, an affected, “slang” flavor to it. The existence of adjectival wicked, however, occasionally leads to some confusion about the New England intensifier use.

For example, during the Superbowl in 2020, Hyundai ran a car commercial featuring characters that were supposed to sound Bostonian. The actors were native to Massachusetts, and performed with exaggerated Boston accents. At one point, one of the characters said, “Wicked car!” to mean something like ‘cool car.’ News outlets reported that New Englanders reacted strongly to it as an incorrect usage. A Boston Globe article (Annear 2020) reported on a Twitter survey, where 71% of respondents agreed that “regionally, ‘wicked’ is most commonly used as a synonym for ‘very,’ beefing up and emphasizing an adjective — not as an adjective itself.” Some quotes from intensifier wicked speakers reproduced in the article are shown in (27)-(29):

(27)“Wicked is not an adjective, it’s an adverb […] Wicked awesome, wicked cold. Nothing is just ‘wicked.’”(28)“I grew up and live on Boston’s North Shore […] Wicked cool. Wicked psyched. Wicked good. You get the picture. Never used it or heard it used any other way. To say ‘wicked car’ is wicked dumb.”(29)“Here wicked equals very/really, etc., which isn’t the case most other places. ... You can certainly use it as an adjective here, but that’s the universal use. The ad, trying to be Boston, goofed.”

An article in Slate said much the same thing:

I admit I laughed a lot at the gag, though I do take issue with how the ad incorrectly used the word wicked to directly modify the noun car. […] you would say “wicked good car” or “wicked bad car,” but never “wicked car.” Or is Hyundai trying to tell us that the new Sonata is, in fact, a wicked car, its smart park feature powered by dark magic? That is the only logical conclusion.

Page contributed by Jim Wood on June 13, 2024; edited by Sarah Sparling

Please cite this page as: Wood, Jim. 2024. Wicked. Yale Grammatical Diversity Project: English in North America. (Available online at http://ygdp.yale.edu/phenomena/wicked. Accessed on YYYY-MM-DD).